The magic of wobble // A short history of jelly. Part II

Before I started to learn about the history of jelly, I thought that for something to be called jelly, it needs to have gelatin in it, which is obtained from animals. However I was wrong. According to Oxford Companion to Food jelly is type of dish “[…] made from flavoured solutions mixed with a setting agent, and then allowed to cool“. As it turned out the setting agent doesn’t have to be gelatin, it can come in many forms. So today I will try to explore the alternatives.

Gums

Natural gums are a type of liquid that oozes out of tree stems and branches to prevent infection when it has been wounded. It also can be obtained from seaweed and certain seed pods. Gums contain high amounts of sugar and are linked to the pectins and unlike resin they are soluble in water, but not in alcohol nor ether. Gums have many different uses in various industries, including textile, printing, pharmaceutical and food. While most gums in the culinary world are used for same purposes (thickening, stabilising, emulsifying) each have a different molecular structure and gelling property and hence impart different texture to the dish.

There are many types of gums and gum arabic (also known as acacia gum and Senegal gum) is probably one of the most well known. It is the earliest known gum, dating back to the times of the ancient Egyptians when it was already used among other things for paint, cosmetics and even mummification. The Europeans discovered gum arabic through the Arabic trading ports, hence the name. Another popular gum was gum tragacanth (also known as gun dragon). It comes from the genus Astragalus trees that grow in parts of Turkey and Middle East. Gum arabic comes from Mimosoideae family trees that grows in North Africa, Arabia and North West India. The gum is harvested between January and March. To do that one must first slash the bark and tear strips off. That will encourage the sap to start to ooze out and, upon being exposed to oxygen, it will harden. It is then pulled off the tree, dried and bleached in the sun. In the past it was sold as is or powdered, however now the dried gum is often chemically treated to achieve different properties. In culinary it can help to strengthen jellies, preventing sugars from crystallising (think ice-creams) or thicken and emulsify sauces. Gum arabic can be found under the E414 on the ingredients list and gum dragon under E413.

Almond and cream jelly recipe from Hannah Glasse cookbook The Art of Cookery made plain and easy from 1796

In the 17th, 18th and 19th century English cookbooks I looked at the most popular culinary use for both gum arabic and gum dragon was in confectionery. The most common recipes were for cake icing, flower preservation, hard candy or lozenges and for comfits (spices or seeds that slowly have been coated in sugary gum syrup). I didn’t manage to find many jelly recipes with gum arabic. In fact the only recipe that I did find was set with a combination of gum arabic, gum dragon, hartshorn and ivory. By using a combination of all those setting agents the end result would have been a very strong jelly.

Other popular gums are Xanthan gum (made in a petri dish by fermenting sugars with a bacteria called Xanthomonas campestris), locust bean gum (gum extracted from carob tree seeds and often found in vegetarian jelly powders) and chia seeds (most commonly used as a thickening agent in hipster puddings and jams).

Seaweeds & lichen

For me one of the most surprising ingredients that is used as a setting agent for jellies comes from seaweeds. I feel somewhat confident to say that for most of the Western cultures nowadays seaweed associates with sushi and maybe dashi stock, however certain types of seaweeds harbour a secret. In the context of jelly making there are two types of seaweeds that are used – red (agar-agar and carrageen) and brown (alginate).

Lemon jelly recipe from Broadlands Cookery Book by K. E. Bahnke, E. C. Henslowe from 1910

Agar-agar (also known as kanten, Japanese isinglass, Ceylon moss, China moss) is a Malay name for variety of gum hailing from Japan. It is a gum that traditionally is made from red seaweeds of the genus Gelidium. It started to be used as a gelling agent in Japan in the 8th century AD, however only in the 17th century a purification method was discovered. The story talks about a forgetful innkeeper by the name of Minoya Tarozaemon who left a bowl of tokoroten (noddles made from jellied broth) outside his inn. Over several days sitting outside, the temperatures dropping below freezing during night and above during daytime, the contents had completely dried. At one point the innkeeper decided try to remelt the dried noodles. Once the jelly had cooled he noticed that it had turned white and lost its smell. Over time the Japanese perfected this technique and agar-agar was born. You can read more about the process here. In Europe agar-agar started to appear in the late 19th century. While there are uses mentioned for it in the kitchen, from the sources I looked at the main use was as a medium for growing microorganisms in laboratories. Nowadays in the Western kitchens most often it is found in the pantry of the modernist cuisine enthusiasts, where it is valued for it’s versatility.

Irish Moss jelly recipe from Cassell's Dictionary of Cookery from 1892

Carrageen (also known as Irish moss) is a gum traditionally extracted from Chondrus crispus, a red seaweed that can be found on both sides of the rocky North Atlantic coast, but is most closely associated with Ireland. The name comes from the Gaelic word carrigín meaning little rock. People in coastal regions have been using carrageen for centuries as food and as medicine. From what I gather most often it was referred to as a food source for the poor, particularly in times of failed harvest such as the Irish Potato Famine in the mid-19th century, and nourishment for the sick. It was also used as a traditional remedy for various chest aliments.

It appears that carrageen gained more widespread popularity in the 1830’s as a good substitute for arrowroot, sago and other similar thickeners. The 19th century cookbooks often have recipes for Irish moss, however these dishes were mostly aimed at children, the elderly and the sick. It wasn’t until the 1940’s that its popularity exploded. During the WWII Japan banned the exports of agar in fear that the allied forces would use it in search of biological weapons. So the European focus shifted to their own local seaweeds and carrageen provided the answer.

Today carrageen is well known in many industries. It generally has three primary uses - as a thicker, as a stabiliser and as an emulsifier. You can probably find it in various products around home such as ice creams, salad dressings, sauces, beer and wine and even personal hygiene and cosmetic products. If you want to look for carrageen in the ingredient list on the package, most likely you will find it under the E number E407.

To use the carrageen for puddings and jellies you first must wash it and soak it for a little while to plump it up. Then add it to your chosen liquid and simmer for a while, so that the seaweed would release a jelly-like substance. Lastly take the seaweed out and let the mixture cool and set. You can find carrageen in dried and powdered form. Nowadays one of the most well known carrageen recipes is that of Carrageen pudding – a sweetened milk pudding enriched with an egg and most commonly flavoured with vanilla.

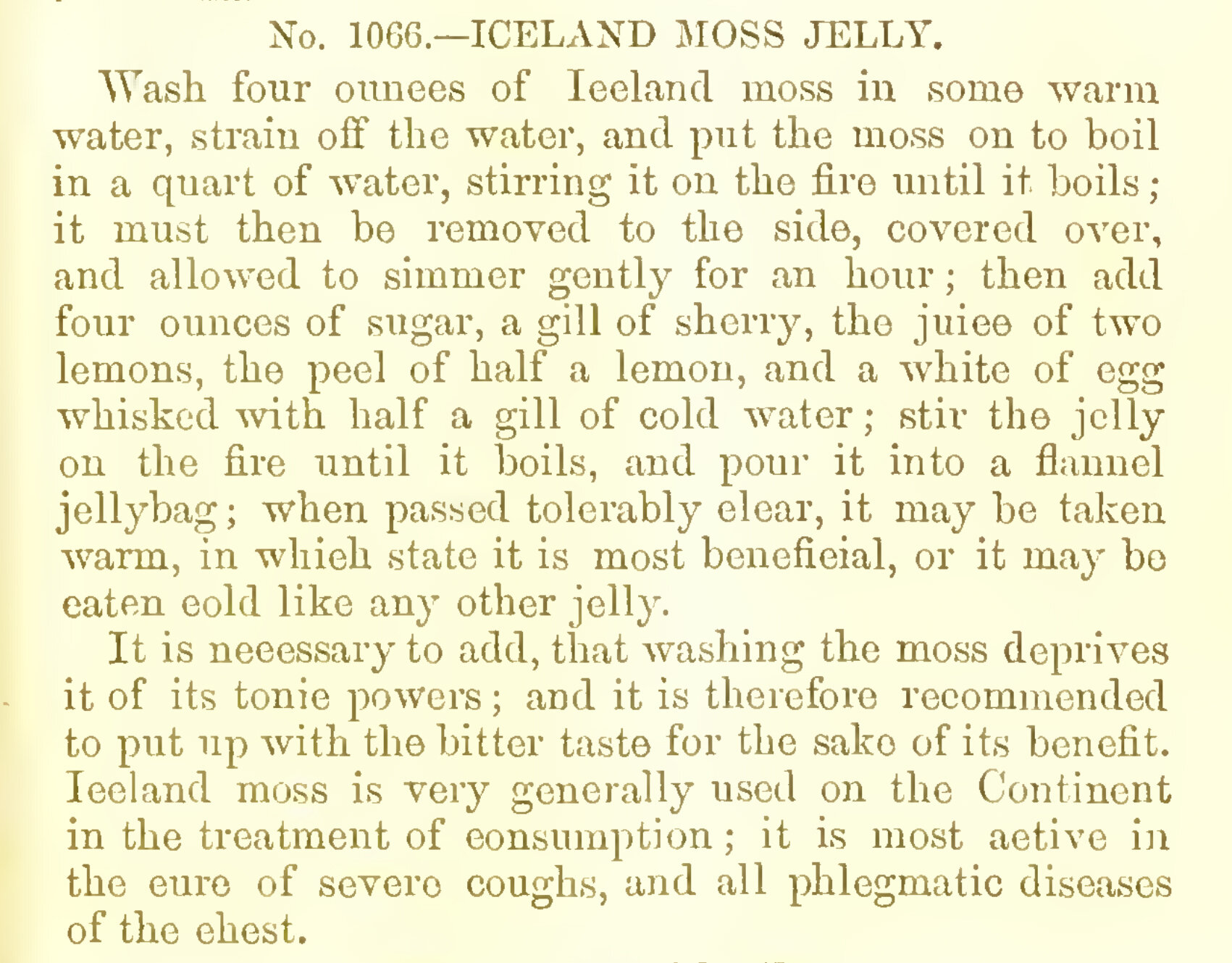

Islandic moss jelly from The Cook's Guide and Housekeeper' s and Butler's Assistant by Charles Francatelli from 1862

Along with Irish moss, Icelandic moss also appears in the 19th century recipes for jellies and as a nourishment for sick. However despite what the name says it is not a moss, it’s a lichen. It grows abundantly in the mountainous areas in northern latitudes. Just like the carrageen, Icelandic moss not only was a source of food in times poor harvests and for the downtrodden but also used as a medicinal herb. It has a very bitter taste in its raw state. To remove it you soak it in water mixed with potassium carbonate or carbonate of soda or boil in lye and then thoroughly wash it. The 19th century books talk about different uses for the Icelandic moss besides jelly, for example, turning it into flour to make simple unleavened breads, as an addition to soups and chocolate and even as a base ingredient for alcoholic spirits.

Alginate is a gum extracted from the brown seaweeds, such as the Californian kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera, and oarweeds of the genus Laminaria. Just like many other gums with the advent of processed food industry, alginate has become increasingly common. However, they are not commonly used in home kitchens.

In fear of making this article any longer I will stop here for now. In part three of my jelly exploration journey I will look at the last two groups of setting agents – starches and pectin.

Sources

Books

Bahnke, Kate Emil, Henslowe, E. Colin, Broadlands Cookery Book, 1910

Brears, Peter, Jellies and their moulds, Prospect Books, 2010

Cassell's Dictionary of Cookery, Cassell Petter & Galpin, 1892

Church, A. H., M.A., F.R.S., Food. A Brief Account of Its Sources, Constituents, and Uses, Chapman and Hall, Chapman and Hall, 1889

Davidson, Alan, The Oxford Companion to Food, Oxford University Press, 3rd Edition, 2014

Davidson, William, M.D., M.R.C.S.E., A Treatise on Diet Comprising the Natural History, Properties, Composition, Adulterations and Uses of the Vegetables, Animals, Fishes etc. Used as Food, John Churchill, 1843

Encyclopædia Britannica, James Moore, 1792

Francatelli, Charles, The Cook's Guide and Housekeeper' s and Butler's Assistant, Richard Bentley, 1862

Glasse, Hannah, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, 1796

Gothard, Barbara Wallace, Lessons on Cookery for Home and School Use, Huges & Co., 1878

Nott, John, The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary, C. Rivington at the Bible and Crown, 1723

Internet

http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~legneref/botany/gumresin.htm (article accessed on 8thMarch, 2021)

https://naha.org/naha-blog/the-difference-between-resins-and-gums-for-aromatherapy-use (article written on 10thFebruary, 2020 and accessed on 8th March, 2021)

https://gumstabilizer.com/agar-agar-in-vegan-jelly-candy/ (article accessed on 10th March, 2021)

https://www.ballymaloe.ie/recipe/carrageen-moss-pudding (article accessed on 10th March, 2021)

https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=237 (article written on the 30th September, 2008 and accessed on 8th March, 2021)

https://blog.modernistpantry.com/advice/agar-vs-the-world/ (article accessed 8th March, 2021)

https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/xanthan-gum (article written on 27th May, 2017 and accessed on 10th March, 2021)

Interesting articles

https://jeremybutterfield.wordpress.com/2014/09/18/chewing-gum-and-the-pharaohs/